S-Meter Calibration

If you only do casual operating, you probably don’t need to calibrate your S-meter. This also applies to contesting, as the signal report for most contests has evolved to 59 for Phone and 599 for CW.

On the other hand, if you’re doing scientific research (for example, monitoring signal strength during a solar eclipse like the one that occurred on August 21 of this year) or comparing antennas on the air, then it’s important to make sure your S-meter is calibrated.

What does “calibrating your S-meter” mean? It means knowing exactly how many dB there are between each S-unit. It also means having an anchor point in terms of absolute power. This anchor point is generally accepted to be S9.

But why do we have to go through a calibration procedure? Didn’t Collins Radio make 6 dB per S-unit and S9 = 50 microvolts (-73 dBm into 50 ohms) a standard?

It’s true that Collins did have those values as a standard a long time ago. I believe many individual manufacturers did adhere to 6 dB per S-unit in the early years, but this fell by the wayside because there wasn’t an official document that new manufacturers signed up to. In 1981 the IARU (International Amateur Radio Union) even adopted the Collins standard as a recommendation. Unfortunately a recommendation has no teeth to it.

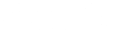

How do the S-meters on modern receivers compare to the Collins standard? Figure 1 gives tabular data (power in dBm versus S-meter reading) for three of my receivers on 20-Meters. Figure 2 graphs this data. These three receivers do not have a separate preamp switch, so all that is noted is the setting of the attenuator.

Three conclusions can be made from this data.

-

The TS-180 comes closest to the anchor point of S9 = -73 dBm. The other two receivers are off by 7 dB (one is higher, one is lower).

-

The TS-180 and the FT-747 exhibit approximately 5 dB per S-unit down to S3. The OMNI-VI is also about 5 dB per S-unit down to S4, but then takes a radical jump of 10 dB from S4 to S3

-

Below S3, the S-meter on all receivers is only 2-3 dB per S-unit.

This data highlights why you need to calibrate your receiver if you’re doing any kind of serious work. For example, if you’re comparing antennas and one antenna is S2 and the other antenna is S1, you might conclude that the gain difference is 6 dB per the old Collins standard. But by knowing the calibration, the real difference in gain is only 2-3 dB.

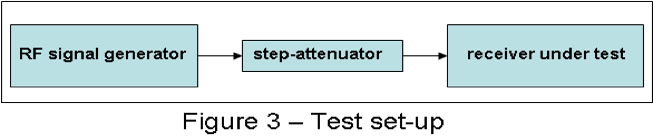

How do you calibrate your S-meter? The best way is to use a calibrated RF signal generator and a step-attenuator. Leave the receiver AGC on (otherwise the S-meter won’t work). Note the power in dBm at each S-unit value. Also record the attenuator setting and/or preamp setting. You may even want to take data at different combinations of the attenuator and preamp (if your receiver has separate controls). Note the power in dBm at each S-unit value. Figure 3 shows the test set-up.

Finally, you should calibrate your S-meter on the different bands to be totally accurate. A good example for doing this is my OMNI-VI - on 160-Meters the delta between S-units is a dB or two different from the 20-Meter data, and the absolute power at S9 is several dB different compared to 20-Meters.